Prof Bobby Duffy – Professor of Public Policy and Director of the Policy Institute, Kings College London

Dr Paolo Morini, Research Fellow, Policy Institute, Kings College London

Crises of public confidence in the police have, sadly, been a recurrent theme in recent years, often around high-profile failures or a general lack of faith in police effectiveness in preventing or dealing with crime.

However, there are two realities behind this that are much less well recognised.

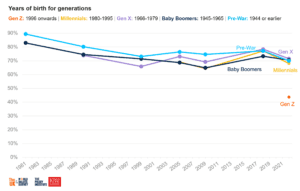

First, as the chart below shows, the decline in confidence in the police is real – but it’s not new. Rather, this is a long-term, chronic condition, where confidence has fallen in steps from 81 per cent overall in 1981 to just 67 per cent by 2022.

These data are from the World Values Survey – the largest social survey in the world, run in the UK by the Policy Institute at King’s College London. This type of long time series is vital in showing this is not a one-off, acute crisis of trust, but a ratcheting down in stages. The pattern here mirrors other data, such as the Crime Survey for England and Wales, including showing a rare upward tick between the 2000s and 2010s, as the concerted focus on neighbourhood policing and confidence targets seemed to have at least some effect.

This suggests decline is not inevitable – but also shows the prolonged effort required, as opposed to the current tendency to consider action in relation to each individual incident. This is a much more endemic challenge.

Percentage who say they have a great deal/quite a lot of confidence in the police by generation

[Click on image to see full chart]

However, there is one important – and startling – new feature to this, which is just how low confidence in the police is among Gen Z, who are the youngest adult generation, aged around 15 to 28 at the time of the survey: only 44 per cent say they have confidence.

This is unusual in three important ways.

First, it’s not just the case that Gen Z is simply more distrustful of institutions in general. There is a common myth about young people that they enter adulthood more suspicious than older generations. The police and the courts are the two institutions where Gen Z’s level of confidence is most significantly lower than the population as a whole. In contrast, Gen Z has similar levels of confidence in parliament and political parties compared with older generations. This is something specific: faith in criminal justice institutions is a key problem for younger generations.

Second, it’s also the first time we’ve seen this pattern among young people in the UK for the police: the trend is long enough that we can see when Millennials (born 1980-1996) and Gen X (born 1966-1979) entered adulthood, and they were no different from older generations.

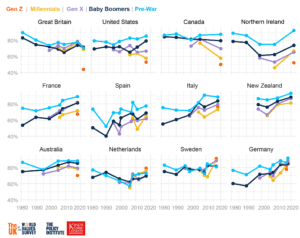

The third way this is unusual is that this pattern – of just one generation of young people being so different from the rest – is not seen in other countries. The World Values Survey covered around 85 nations in this latest study, and the UK is the only one that shows this pattern, as the chart below makes clear. Some countries, notably the US, are arguably in a worse position, with confidence relentlessly falling generation-on-generation, with each new cohort having less confidence than the last. Others, however, like Sweden and Germany, show no differences between the generations, and even increasing levels of confidence overall.

Confidence in the police – different generational patterns

[Click on image to see full chart]

So why is this happening in the UK? Given it’s just emerging, this specific pattern has been little explored, but we do know from other work that it’s likely to be a mix of direct experience and what young people see and hear indirectly, including through their social media consumption.

Gen Z does have much higher social media use than older generations, with around nine in 10 using it every day, compared with around half of Gen X (those in their forties and fifties). They will therefore have been more exposed to high-profile incidents of police failings covered extensively on these platforms, and will have had greater engagement with movements that originated in the US, such as Black Lives Matter and Defund the Police.

These high-profile incidents and emergent movements are likely to have a greater impact on younger people, not just because of greater exposure, but because they are at a more formative stage of life, where views are more malleable.

This younger generation has also grown up through a time of constrained police budgets and general withdrawal of policing from the community, which is likely to have left a relational vacuum compared with earlier generations: there is much less grounding in personal experience to protect the police from negative impacts to their reputation from high-profile incidents and campaigns.

But personal experience will also play a role, and their interactions with the police are often not positive: two-thirds of all stop and searches in the year ending March 2022 were carried out on people aged between 10 and 29 years old, which is a pretty close match to the current Gen Z age range. Of course, stop and search only directly affects a relatively small proportion of young people, where their experience of crime reporting, crowd control and even online interactions will all affect perceptions – but the indirect effects from the sharing of negative stop and search experiences with friends, and the coverage of this online, will also be significant.

So what do we do? There are broadly two groups of interventions.

First, perceptions of procedural justice are known to be vital to confidence in the police, which means that focusing on stop and search will be important. For example, Crest Advisory has called on the Home Office to establish an independent national taskforce that could drive improvements in stop and search practices by developing minimum standards in training, guidance and vetting of officers, as well as communication and engagement with communities in which stop and search powers are frequently used.

It also recommends that community scrutiny panels – which allow community members to review individual police interactions with the public – recruit young people who have been stopped and searched, in an effort to ensure the panels are representative of those most affected by the practice.

Which points to the second group of actions – greater community engagement more generally, and in this case specifically with young people. The Police Foundation’s 2022 Strategic Review of Policing outlined the strong evidence for the effectiveness of community policing in improving public confidence in the police – but highlighted that such engagement with local neighbourhoods has been cut back significantly since 2010. It called on the Home Office to ask police forces to deliver a “substantial uplift” in community policing. Initiatives such as those involving youth voices to shape the Police Race Action Plan could help in engaging and listening to younger generations.

But while this is an obvious aspiration, there is also a need to be realistic about what can be achieved given strained public finances and competing policy priorities. There are pockets of good practice across the country but efforts need to be more systematically evaluated and applied. A clearer picture is needed of what works, with more rigorous testing and piloting of interventions, followed by greater joining up and coordination of police-youth engagement efforts that are shown to be effective.

Whatever we do, we need to act quickly and decisively, or risk embedding the pattern of generation-on-generation decline that we see in the US – the UK model of policing by consent would struggle to survive that sort of baked-in downward pressure on public confidence.